This piece was commissioned then declined, in part for its lack of our old friend ‘balance’. So here it is, in case it’s of interest. It’s addressed in particular to artists and musicians who might be pondering their role in movements for social and ecological justice…

Musicians are mavericks. We might hear the call to join this movement or that, and hesitate. So when the call comes in to be part of a movement of artists responding creatively to climate change, (a human and ecological catastrophe-in-progress), what might some of the questions be ricocheting around the head of a pondering musician?

“Do I have something to offer that would be any use?”

“Would it rob me of my autonomy as an artist?”

“Might I be pigeon-holed as an eco-lunatic or social justice-bore?”

“Might I be ostracised by my more fearful peers?”

And last but not least:

“Might I miss out on that tasty commission and see my career slip out of sight?”

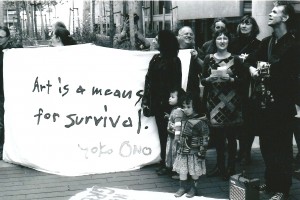

Those are all justifiable questions, but if we were to see our role as creating extraordinary and unique art in the service of the collective and the planetary, perhaps they would seem a little less pressing? Being a part of Art Not Oil, working to end oil industry sponsorship of art and culture, I’ve looked at those questions again and again, because I don’t want to be part of a progressive movement for social and ecological transformation that doesn’t have art – and particularly music – at its heart. It’s also radiantly clear to me that when music is made which burrows bravely into these tragic, ridiculous and possible times, new doors and windows appear. It seems to be extraordinarily hard to do well, but at its best such music helps me not to do what part of me longs to do, which is to turn away from the perilous place we inhabit as a species, from our misplaced interconnectedness, and the murderous way our species has with its compatriots. Such music could be mournful, resistance-celebrating, wordlessly informative, cinematically Antarctic, swingingly poetic, scabrously satiric, or irresistibly danceable…The more diverse the approaches the better.

Having said all that, it’s perfectly possible of course to call publicly for an end to oil sponsorship without being a musician who makes work about these issues. And a third alternative is to take an apolitical piece and perform it in a contested space, for example in front of the Shell ‘memorial’ in the Royal Festival Hall (left).

Early in 2013, a group of activists and musicians came together to form Shell Out Sounds (SOS), compelled to lever Shell out of its profitable position as sponsor of the Southbank Centre; (I say ‘profitable’ because good PR means a smoother ride when it comes to public opinion, and, more importantly, the opinion of the movers, shakers, potential Shell-critics and ABC1s who make up much of the SBC’s audience.) SOS is also compelled to use music as its tool, for convincing strategic reasons, and because we get to have a hell of a lot more fun than mutely holding a placard. We’re all complicit to some degree, caught up in this fossil fuelled ‘civilisation’ but still trying to fumble in the near-dark towards a fairer, post-oil way of living.

Early in 2013, a group of activists and musicians came together to form Shell Out Sounds (SOS), compelled to lever Shell out of its profitable position as sponsor of the Southbank Centre; (I say ‘profitable’ because good PR means a smoother ride when it comes to public opinion, and, more importantly, the opinion of the movers, shakers, potential Shell-critics and ABC1s who make up much of the SBC’s audience.) SOS is also compelled to use music as its tool, for convincing strategic reasons, and because we get to have a hell of a lot more fun than mutely holding a placard. We’re all complicit to some degree, caught up in this fossil fuelled ‘civilisation’ but still trying to fumble in the near-dark towards a fairer, post-oil way of living.

Our performances often coincide (weirdly) with those that bear the tainted title of ‘Shell Classic International’. Sometimes we rewrite existing pieces, and sometimes we use new material.

When we’re engaging in these various acts of harmonic disobedience, taking care not to stand in the way of musicians earning their living, we often have friendly conversations with security and other staff, some of whom have been known to give us a surreptitious wink of support. Concertgoers range from the apoplectic to the delighted via a smattering of the bemused who have (happily) missed the Shell logo on the programme, or who (less happily) have no clue why singers might be unhappy with Shell.

November saw us sing ‘Oil in the Water’, a rewrite of the still-potent spiritual ‘Wade in the Water’ in the Royal Festival Hall, just as the Sao Paolo Symphony Orchestra (under Marin Alsop) was due to take the stage and begin a ‘Rest is Noise’ programme that included Berio’s tribute to Martin Luther King. We were astonished to find ourselves applauded, having prepared for heckles and boos. King had given us courage with his statement that “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.”

The day after that performance, a group of artists, musicians and authors who have all performed at the Southbank Centre signed a letter calling on it to drop Shell sponsorship on the 18th anniversary of the execution of Ken Saro-Wiwa and the Ogoni 9. One of the signatories, composer Matthew Herbert, commenting in the Guardian earlier this year, said: “If were to look back from 100 years hence at the art being produced now you would find it quite hard to deduce that there was a global financial meltdown, that there was an Arab spring going on, an environmental catastrophe underway. There’s a really unhealthy point where music and art instead of trying to prick the bubble, become the bubble, and that particularly music seems happy to become a soundtrack to consumption – that’s very dangerous really.”

In March 2014, Shell Classic returns to the RFH. As of December 2013, we have a little time to plan something innovative and arresting (though not arrestable), and would welcome offers of collaboration from composers, musicians and others who feel moved to act. More widely, it would be wildly inspiring to see musicians and other artists maybe blazing a trail, maybe tiptoeing towards an uncertain future, or maybe just adding their name to the list of those calling for an end to oil industry sponsorship of the arts.